Shakespeare According to IQBAL

by Khurram Ali Shafique

| Come unto these yellow sands, And then take hands; Curtsied when you have and kiss’d, The wild waves whist, Foot it featly here and there, And, sweet sprites, the burden bear. Hark, hark!

Ariel’s Song, Act I, Scene 2 Man is not the citizen of a profane world to be renounced in the interest of a world of spirit situated elsewhere. Dr. Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), |

| Preface

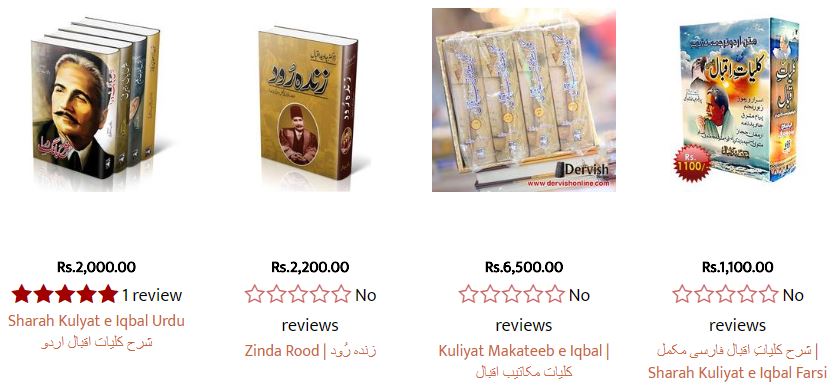

The world had been at war for two years when the third centenary of William Shakespeare arrived in 1916. Sir Israel Gollancz of Kings’ College and Shakespeare Memorial Theatre compiledA Book of Homage to Shakespeare. One of the entries was from Dr. Sheikh Muhammad Iqbal (later Sir), an Urdu poem comprising of fourteen lines – the same as in a Shakespearean sonnet but following a different rhyme scheme. The homage in the last couplet was rather unusual for those days: Nature guards its mysteries so jealously, This may pose a problem if we know what else the poet was writing around that time. Since last September, he was in the thick of a controversy for attacking Plato, theological mysticism and decadent literature in the first installment of a long Persian poem, Secrets and Mysteries.Just as the Book of Homage first appeared in England, Iqbal was writing the second part of his long poem in Lahore. This was dedicated to ‘The Muslim Nation’, and he claimed in the dedicatory epistle that for quite some time he had been singing praise of no one except this true love, his nation. This was not poetic exaggeration, according to him, since in the last chapter (written about a year later) he would request the Holy Prophet to be a witness that his poetry contained nothing but the Quran. If so, then how come he had chosen to surpass many in paying homage to Shakespeare? Why was he placing the English poet in the same category as Rumi? This is the first of the intriguing questions that arise as we approach Shakespeare from the perspective of Iqbal. Attempts at comparative study of Shakespeare and Iqbal have been curiously very few – despite the impressive bulk of literature produced about Iqbal. Practically no attempt has been made at reinterpreting Shakespeare in the light of Iqbal’s views. This little book attempts to do that now. |

| 1. Seven Stages of the Potent Art

Was Shakespeare everything and nothing, or was he everything and himself? In the first case he could not have had a self, and hence unable to capture in a single instant the fullness of his entire past: his memory must have been a chaos of vague possibilities rather than a summation. On the other hand, if he had a self, then possibilities of other kinds must have been open to him, and we may know them by reflecting on the story of Prospero. 1. The exile of Prospero For Prospero, the Duke of Milan, books became what the Forbidden Tree was for Adam and Eve, and Joseph’s dream for Joseph. They preoccupied him, so that in spite of immense popularity among his people he could not retain the dukedom, which was then usurped by his brother Antonio with the help of Alonso, the King of Naples. Prospero got exiled and Milan became a vassal of Naples. Thus was Milan thrust from Milan, that he may find a kingdom where he himself was lost. 2. The liberation of Ariel Sycorax, an old witch from Algiers, had been left by some sailors on an uninhabited island and bore a son whose personality resembled some art and literature of a few centuries later: “as disproportioned in his manners as in his shape.” Through her magic, the witch subdued Ariel, a free spirit, and confined him into a cloven pine when he refused to obey her earthy and abhorred commands. She died, leaving behind Caliban as the sole heir while Ariel groaned in pain until Prospero arrived on the scene a dozen of years later, newly banished from Milan with his three year old daughter Miranda and some of his books that had been slipped into the luggage by a kindhearted Neapolitan Gonzalo. The recruitment of elves, demi-puppets and other inward forces of Nature, and the liberation of Ariel through the breaking of the spell of Sycorax were a sharp reproof to those degenerate days and the earliest evidence of that learning which Prospero had acquired at the cost of dukedom. 3. Miranda’s coming of age Caliban, who was taking Prospero around the island, and in return was being looked after by him and taught language by Miranda, attempted to rape the young woman as she came of age. The father intervened and the subsequent enslavement of Caliban proved the wizard’s capability in a manner that even Caliban could appreciate: “his art is of such power, it would control my dam’s god Setebos.” Miranda, the heroine of Shakespeare’s play The Tempest is the gift of language and may personify his literary output – offspring of his verbal art, his “brainchildren”: his plays and poetry. Fortunately, Caliban is not the only suitor. 4. Ferdinand’s courtship Ferdinand, the son of King Alonso, appears on the island when a storm at the sea is engineered by Prospero through Ariel: all travelers are saved and Ferdinand is led by the song of the elements to set eyes on Miranda. She perceives him as a spirit and thinks there is no more such shapes as he while he, although he must have seen other such shapes as she, is helped by the power of love to foresee in her an ideal spouse: he proposes less than twenty lines later (“O, if a virgin, and your affection not gone forth, I’ll make you the Queen of Naples”). Aside, Prospero exclaims to Ariel with unusual excitement, “Spirit, fine spirit, I’ll free thee within two days for this.” In front of him are not further proofs of his art but its very principles laid bare: channelling free will through systematic arrangement of circumstances is like rethinking the thought of Divine Creation. 5. Gonzalo’s awakening Sebastian, the brother of King Alonso, is tempted by Antonio to assassinate the monarch, since the entire entourage except Sebastian and Antonio has fallen asleep at an odd hour. The plot is thwarted when Gonzalo is woken up by Ariel, who had earlier induced the untimely sleep on instructions from his master Prospero. Preventing the original sin, while the good Neapolitan Gonzalo stands proxy for the wizard: here is a psychological reality to hold, as it were, the mirror up to the social reconstruction dreamed by Gonzalo just before going to sleep: “I’ the commonwealth I would by contraries execute all things… All things in common nature should produce without sweat or endeavour. Treason, felony, sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine would I not have…I would with such perfection govern, sir, t’ excel the Golden Age.” 6. Stephano’s plot Caliban inspires Stephano, the drunken butler of the King, to assassinate Prospero, become the “king” of the island, force Miranda to become his queen and appoint Caliban and Trinculo as “viceroys”. This is prevented when Prospero and Ariel set their spirits, in the form of dogs and hounds, on the conspirators. Caliban’s true nature is now revealed (as long as we can read and eyes can see) but unlike other such incidents, this one wasn’t initiated by Prospero. Destiny had intervened, like at the time of the initial banishment (which Miranda does not remember: “Never till this day saw I him touch’d with anger so distemper’d”). 7. The breaking of the staff Ariel and spirits have appeared in front of King Alonso and his companions, declared themselves to be “ministers of Fate” and reminded the guilty of their sins. The conscience of Alonso is woken up: Ferdinand shall marry Miranda, through whom Prospero’s descendants shall rule over Naples, which thus inherits Milan lawfully and Antonio is left without any such legacy. Everybody shall go home, Prospero break his staff and burn his books, and Ariel returns to the elements now. That is almost the end, but not quite so. 8. Prospero’s project In the epilogue, Prospero appears and informs you that his project was to please, i.e., to please you. Take him literally, and it gives you an eighth conflict because then you become what Prospero was at the time of being banished from Milan, the play you saw just now becoming to you what books were to him: a preoccupation due to which Antonio, your reason, will banish you from the real world and send you to the island, your imagination – reason cannot believe that reality and imagination could be held together, and even King Alonso (whichever part of you he represents) is going to cooperate since he is yet to know better. This eighth conflict, your banishment, is in fact the first in a second cycle of the same seven sequences, but now you are the protagonist. 9. Characters as conflicts

When Ferdinand arrived on the enchanted island, he was welcomed by Ariel’s Song: Come unto these yellow sands, Ariel was groaning from inside a cloven pine when Prospero first set foot on the yellow sands but the soul of Prospero may have sensed the unheard melody even then (this conflict and the previous one do not occur on stage but only in the soul of the protagonist since these conflicts are outside the memory of Miranda, the protagonist’s craft, which is still at an early stage of development). From the third conflict onward, the message of each conflict is represented by a character in the play and its refutation by another:

|

2. Twice Upon A Time

Seven princesses, one from every realm of the inhabited world, had been preordained for Behram V of Persia. He built a dome of different colour for each beauty, visited one on each night of the week and listened to a story by her. He repeated the cycle many times.

This is how the Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi (c.1141-c.1209) turned history into legend in his long poem Haft Payker, or Seven Beauties, in the late twelfth century.

“That which is new and old at the same time is language, and now I use language to show this,” said Nezami in the preface. “The Divine command on the Day of Creation did not produce anything more charming than language. Do not consider those who have this gift, ever to be dead: they are like fish, having lowered themselves just beneath the surface of speech: they shall reappear sooner than you utter their names… Language, if its soul is untainted, is the keeper of the treasury of the unseen: it knows the story that has not been heard and reads the book that has not been written.”

The following is a synopsis of the seven stories narrated by the princesses, and you may observe that the stories comprise of essentially the same conflicts, feature the same roles and were narrated in the same order as the seven major conflicts that formed the storyline of The Tempest (Language knows the story that has not been heard and reads the book that has not been written).

- THE BLACK DOME (the exile of Prospero). A king leaves his kingdom out of curiosity about a black dress worn by someone, and arrives in a city where everyone wears black but nobody explains why. He has to find out by himself: thrown into a magical realm where he is led on by a beautiful maiden without being allowed to consummate his desire and then thrown out forever when he is beyond himself. He starts wearing black too.

- THE YELLOW DOME (the liberation of Ariel). True love between a king and a slave girl is challenged by their inherent insecurities that are fuelled by a foolish old maid until love conquers all.

- THE GREEN DOME (Miranda’s coming of age). Bashr, literally meaning “the human being” in Persian, takes fancy on a fair woman but then meets a beastly character whose animal instincts cannot be tamed before they lead him to a pathetic death. The despicable character leaves behind a beautiful widow, who turns out to be none other than the woman sought by Bashr. She is herself too happy to get rid of the beast.

- THE RED DOME (Ferdinand’s courtship). A chivalrous young man wins the hand of a princess after going through a series of tests that involve moral as well as physical strength.

- THE BLUE DOME (Gonzalo’s awakening). A traveller is caught in a labyrinth of frightening situations, only to realize that they are happening in his imagination and he needs to “wake up.”

- THE SANDAL-COLOURED DOME (Stephano’s plot). A character called “Bad” usurps the ration of his fellow-traveller “Good” and attempts to murder him but ends up being chased and killed by the barbaric father-in-law of “Good.”

- THE WHITE DOME (the breaking of the staff). A young man enters his own garden through the backdoor, finds unknown women feasting there and takes one of them to a secret chamber. When asked who she is, she whispers, “Fate.” The chamber falls apart and other accidents prevent the man whenever he tries to consummate his desire until he realizes that he must marry the woman first.

“It’s a locked up case of pearls, and I have hidden the key in the text,” Nezami says about his book in the epilogue. “The pearl glides on a string to which the loosening of knots is the key. All that is good or bad in its verses is invariably an allusion or a hint for Reason. Each separate story has become a house of treasures.” Then he reminds the king who was his patron:

May I submit with due humility, if it does not offend: though your banquets are gorgeous, the banquet that lasts forever is this one. Of all things that have been called gems and treasures, this brings ease whereas those others give nothing but pain. Even if they should last five hundred years – may you live long – they shall decay, whereas this treasure as a special court shall be with you till the end of Time.

Nor marble nor the gilded monuments of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme, but you shall shine more bright in these contents than unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time.

The Seven Beauties is the fourth masnavi (long poem with rhymed couplets) in a set of five written by Nezami, collectively called Khamseh, or the Quintet:

- The Treasure of Mysteries (Makhzanul Asrar)

- Khusro and Shireen (Khusraw-o-Shireen)

- Layla and Majnun (Laylee-o-Majnun)

- Seven Beauties (Haft Paykar)

- The Epic of Alexander (Iskandernameh)

In The Tempest, the latter five conflicts are personified by characters of the play. In theSeven Beauties, each of the latter five stories corresponds to one of the five masnavis (and therefore every character of The Tempest which personifies the essence of a story from theSeven Beauties also represents the corresponding masnavi of the Khamseh):

- MIRANDA: The Treasure of Mysteries (Makhzanul Asrar), the first masnavi. This long poem is a list of insights about which the poet says in the prelude, “the substance of spiritual excellence as well as kingship is contained here.” This common substance of spiritual excellence and kingship is personified by the heroine of the third story in theSeven Beauties (told inside the green dome) and by Miranda in The Tempest.

- ARIEL: Khusro and Shireen (Khusro-o-Shireen), the second masnavi. Shireen is an Armenian princess contested between Khusro, the emperor of Persia, and the sculptor Farhad, who commits suicide when the emperor sends him false news about the death of the princess. Sometime after his marriage to Shireen, the emperor shows disrespect to the ambassador of Prophet Muhammad despite knowing from family tradition as well as a dream that collaboration with this last prophet would be the secret power of all kingdoms. He is assassinated and the usurper wants to marry Shireen, who kills herself with a dagger during a nightly vigil on her late husband’s tomb. Shireen, sought by so many suitors, is like the princess in the fourth story of the Seven Beauties (told inside the red dome), except that her suitors are unworthy since they are yet to grasp the secret principles of power, personified by Ariel in The Tempest.

- GONZALO: Layla Majnun, the third masnavi. When the young Arab noble Qais is denied marriage to his beloved Layla, he takes to the wilderness. There he connects with Nature, befriends all creatures and people nickname him “Majnun” or madman: here we have an Arabian precursor of the Neapolitan Gonzalo. When the two lovers die, a tombstone is put on their graves to say that the sleepers will “awake” on the Judgment Day to be united forever – just as the protagonist of the fifth story in the Seven Beauties(told inside the blue dome) needs to be woken up.

- FERDINAND: Seven Beauties (Haftpaykar), the fourth masnavi.While Behram was sitting inside the domes and listening to stories from beautiful women, his vizier was tyrannizing the country, as Behram learnt later through “seven petitioners” (matching the seven stories). This is epitomized in the sixth story itself (told inside the sandal-coloured dome) where Bad steals the baggage of the Good and tries to hurt him. Ferdinand in The Tempest is quite reminiscent of Behram as he watches a masque presented by spirits and plays chess with Miranda inside a cell, just as Behram listens to stories inside the dome. As Behram eventually learns about the misdeeds of the vizier, so Ferdinand has to learn about the misdeeds of his father, the king.

- PROSPERO: The Epic of Alexander (Iskander Nameh), the fifth masnavi. Alexander of Macedon, by his Persian name Iskander, is merged with the Quranic figure of Zulqarnayn, a king whom God granted dominion over the inward and outward forces of the world. “Iskander Zulqarnayn” sets out in search of the Water of Life so that he may live forever but only Khizr, a guide, makes it to the fountain and destiny assigns him the task of guiding the lost travellers till the end of time. In the Seven Beauties, the last story (told inside the white dome) emphasizes the necessity of accepting the natural order of things. In The Tempest, Prospero must break his staff and burn his books, just as Alexander must accept that his kingdom cannot last forever. In the epilogue, Prospero reappears rather like Khizr.

3. The Human Spirit

“When you see two of them meet together as friends, they are one, and at the same time six hundred thousand,” Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-73) wrote about true mentors, some eighty years after Nezami. “Their numbers are in the likeness of waves: the wind will have brought them into number. The Sun, which is the spirits, became separated in the windows, which are bodies. When you gaze on the Sun’s disk, it is itself one, but the one who is screened by the bodies is in some doubt. Separation is in the animal spirit, the human spirit is one essence.” Can we say this about Nezami and Shakespeare, and perhaps also about Rumi, Goethe and Iqbal?

The following note appeared in a Sufi magazine published in Urdu from Meeruth, a city in India, on August 1, 1913:

Dr. Sheikh Muhammad Iqbal dreamed that Rumi was commanding him to write a masnavi. Iqbal replied, “That genre reached its perfection with you.” Rumi said, “No, you should also write.” Iqbal stated respectfully, “You command that the self must be extinguished but I reckon the self to be something that should be sustained.” Rumi replied, “My intended meaning is also the same as what you have understood.”

He [Iqbal] found himself reciting the following verses as he woke up, and then he began to write them down…

Those verses were in Persian, which was the language of Rumi, but the title of Iqbal’s book alluded to Nezami, who had called his first work The Treasury of Secrets. Iqbal named the first part of his masnavi ‘The Secrets of the Self’ and the masnavi itself Secrets and Mysteries.

In the preface, Iqbal repeated claims that were the trade mark of Nezami, such as that his work contained means for spiritual excellence as well as worldly power and that many poets were born after they died, coming back like roses growing from the dust of their tombs (Nezami had compared such poets with fish under water, raising their heads when their names were called). In the works of Iqbal, several characters from Nezami were going to reappear in modern settings – Khizr, Layla, Qais, Pervez and Farhad, among others. Just as Nezami had employed the name of his son, Muhammad bin Ilyas, to represent posterity, so Iqbal was going to address the coming generations through his son (and may have had this end in mind even as he named the child in real life: Javid literally meant “the eternal” or even “eternity,” the subject of Nezami’s last epic).

The poem about Shakespeare, which Iqbal sent for inclusion in A Book of Homage to Shakespeare, is found as an unfinished draft in a notebook used by the poet around this time. The finished version does not exist in facsimile. The poem may have been completed just shortly before being sent to Sir Israel Golancz in 1915 or 1916, and written on a paper that did not come back either from the scribe who scribed it for being sent to England or from the friend who translated it. In any case, Iqbal had been “visited” by Rumi in his dream by the time he sent the poem to Sir Israel.

The original in Urdu, since it has fourteen lines, obviously divides itself into seven couplets (four in the first stanza and three in the second). If translated faithfully, they trace the development of Prospero’s art (and Shakespeare’s) through the same major conflicts that appear in the chronological storyline of The Tempest, the relationship becoming increasingly visible as the poem progresses.

Shakespeare

The exile of Prospero

The river’s flow mirrors the red glow of dawn,

The quiet of the evening mirrors the evening’s song;

The liberation of Ariel

The roseleaf mirrors spring’s beautiful cheek;

The chamber of the cup mirrors the coquettish wine;

Miranda’s coming of age

Beauty mirrors Truth, the heart mirrors Beauty;

The beauty of your speech mirrors the human heart.

Ferdinand’s courtship

Life finds perfection in your skysoaring thought:

Was your luminous nature the goal of Life?

Gonzalo’s awakening

When the eye looked around to see you,

It saw the sun hidden in its own radiance.

Stephano’s plot

You were hidden from the eyes of the world,

But with your own eyes you saw the world exposed and bare.

The Breaking of the Staff

Nature guards its mysteries so jealously,

It will never again create one who knows so many secrets.

This small booklet has been published by Iqbal Academy Pakistan to commemorate the installation of a plaque carrying the translation of a poem by Dr. Sir Muhammad Iqbal at the Birthplace of William Shakespeare on April 23, 2010.

The poem originally appeared in Urdu (with a translation) in A Book of Homage to Shakespeare compiled by Sir Israel Gollancz in 1916.

Iqbal and his community were opposed to the skepticism that dominated the academic horizons of the West after Wolrd War I. Recognition of this alternative perspective now may mark the beginning of a new era in the appreciation of Shakespeare’s work:

Nature guards its mysteries so jealously,

It will never again create one who knows so many secrets.

Source: http://therepublicofrumi.com

by Khurram Ali Shafique